Faux Fungi: The Problem with Truffle Oil

Most commercial truffle oils are chemically flavored with synthetic compounds like 2,4‑dithiapentane rather than actual truffles, which misleads consumers and distorts public perception of what truffles truly taste like.

Fresh truffles possess an unmistakable aroma often described as earthy, musky, garlicky, nutty, or even slightly sweet and floral depending on the species. This aroma is due to a complex blend of volatile organic compounds, some of which are also found in pheromones and forest soils. Truffles are a true luxury, known for their complex aromas and unmatched capacity to enhance the savory taste (umami) of foods. Many chefs have tried to transfer this unique character to their dish, unfortunately fresh truffle aroma is fleeting and does not survive the cooking processes. Some have turned to chemistry and approximate the natural aroma by adding synthetic compounds. Because of its ease of use and relative low cost these artificial oils have become a staple in kitchens and restaurants around the world. But behind its glossy label lies a debate about authenticity, quality, and truth in flavor. While some enjoy the artificial flavor, it tastes little like fresh truffle and is often deceptively labeled, misleading consumers about its authenticity.

What Is Truffle Oil?

Truffle oil is typically made by infusing a neutral or mild-flavored oil—such as olive, grapeseed, or sunflower oil—with the aroma of truffles. In theory, this sounds straightforward. But in practice, the majority of truffle oils on the market do not contain any actual truffle. Instead, they use synthetic aromatic compounds, most notably 2,4-dithiapentane, to mimic the scent of real truffles.

While some producers use actual truffle residues or extracts to flavor their oils, these are rare and often far more expensive. The difference is not only chemical—it’s perceptual, and to many chefs, philosophical.

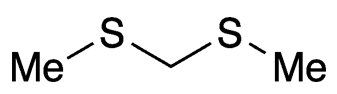

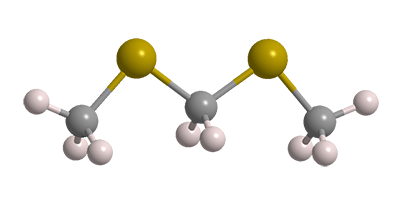

The Role of 2,4-Dithiapentane

The key compound in synthetic truffle oil, 2,4-dithiapentane, is a volatile organic sulfur compound that occurs naturally in some truffle species, such as the black Périgord truffle (Tuber melanosporum) (Essenberg & Trappe, 1983). In the lab, this molecule is synthesized and added to oils to replicate the characteristic truffle aroma. However, real truffles contain a complex bouquet of volatile compounds—up to 200 in some varieties (Splivallo et al., 2011)—which gives them a far more nuanced and layered aroma than synthetic truffle oil.

Synthetic truffle oil provides just one sharp, pungent note, which can be overpowering and often misrepresents the full sensory experience of consuming real truffles.

Culinary Controversy

Many chefs and food experts argue that synthetic truffle oil delivers a misleading impression of what truffles actually taste like. Chef Daniel Patterson (2010) famously criticized it in The New York Times, arguing that “truffle oil is to truffle what Tang is to orange juice.”

Anthony Bourdain was even more direct, calling it “not food” in an episode of No Reservations, reflecting the disdain many professionals hold for the product’s artificiality.

While some chefs still use truffle oil for its ability to add punch to dishes like risotto, popcorn, or mashed potatoes, others reject it entirely, preferring to honor the real flavor of truffles through fresh use or natural infusions.

Infusing Products with Truffle Aroma: Methods and Considerations

Truffle aroma is notoriously delicate and volatile, which makes capturing and preserving it in products like oils, butter, honey, and salt both a science and an art. Whether producers are working with real truffles or synthetic compounds, the goal is to transfer the aroma effectively into a stable medium without significant loss of intensity or character.

Natural Infusion

- Oil: Fresh truffles are thinly sliced or grated and steeped in mild oils at low temperatures (below 50°C). The mixture is stored for 1–2 weeks before straining. This preserves more of the volatile compounds but results in a short shelf life and a higher cost.

- Butter and Salt: Truffle shavings can be directly mixed into butter, or dried and blended with salt. These carriers trap aroma well but degrade over time, especially without refrigeration or airtight storage.

- Honey and Cheese: These fat- and sugar-rich carriers can also absorb and stabilize some aromatic compounds. But again, time is of the essence—aroma begins to fade rapidly after infusion.

Synthetic Infusion

Most commercial truffle oils and products use 2,4-dithiapentane or related compounds to simulate truffle aroma. These are added in microdoses to oil or powder carriers under strict lab conditions for stability and shelf life. While efficient and cost-effective, the resulting flavor is far simpler than that of true truffles (Jeleń et al., 2003).

Encapsulation (Advanced Techniques)

Emerging technologies like cyclodextrin encapsulation and spray-drying are being explored to trap and release truffle volatiles slowly. These approaches aim to enhance shelf life and aroma retention, particularly in processed or packaged foods.

Why Is It So Hard to "Hold" the Authentic Truffle Aroma?

Even with the best intentions and methods, authentic truffle aroma is notoriously difficult to preserve. This challenge comes down to the chemistry of the aroma compounds and their sensitivity to environmental factors.

Volatility and Reactivity

Truffle aroma is made up of dozens of volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—such as dimethyl sulfide, methanethiol, and 2,4-dithiapentane—that are:

- Extremely volatile (evaporate easily)

- Chemically reactive

- Heat- and light-sensitive

As a result, they degrade or evaporate rapidly during food processing, cooking, and storage (Splivallo et al., 2011).

Complexity and Sensory Synergy

Real truffle aroma relies on a delicate balance of many compounds acting together. If just a few degrade, the aroma loses its richness. This makes natural truffle flavor extremely fragile—unlike synthetic truffle oil, which contains only one or two dominant notes (Jeleń et al., 2003).

Biological Changes Post-Harvest

Fresh truffles are still alive after harvesting. They undergo enzymatic and microbial changes that alter their aromatic profile. Even under refrigeration, truffles begin to lose aroma within 5–10 days (Strojnik et al., 2010).

Sensory Volatility

The most striking truffle aroma effect happens when truffles are freshly shaved over warm food. The heat activates volatile release in a way that infused or cooked products cannot replicate. This leads to a perception gap—products may technically contain truffle but smell or taste like very little.

Truth in Labeling: Transparency Over Trickery

Whether synthetic or authentic, what matters most is honesty. With truffle products—especially oils—many consumers are unaware that what they’re tasting may have little or no real truffle in it. This is where the importance of truthful, clear labeling becomes paramount.

Misleading Language

Common phrases like “truffle infused,” “truffle flavored,” “aroma” and “natural flavor” can confuse consumers. While technically compliant with some regulatory frameworks, these terms are often used to imply an authentic connection to real truffles that usually does not exist.

In many cases, the product contains only lab-synthesized aroma compounds, with no trace of actual Tuber species. For consumers seeking the experience of real truffles—or trying to avoid artificial additives—this lack of clarity is problematic.

Labeling Guidelines and Best Practices

Proper labeling isn’t just ethical—it helps preserve consumer trust and encourages informed choices. Here’s what responsible truffle product labeling should include:

- Specificity: Clearly identify the source of aroma compounds (e.g., “contains artificial truffle flavoring” vs. “infused with Tuber melanosporum extract”).

- Ingredient Transparency: List exact truffle species used (if any), along with percentage or origin where applicable.

- Avoidance of Deceptive Imagery: Don’t use photos of fresh truffles on products that contain only synthetic flavoring.

Regulatory agencies such as the FDA (in the U.S.) and EFSA (in the EU) require that artificial flavors be declared in the ingredients list, but the enforcement of labeling accuracy can be inconsistent. Voluntary industry standards or third-party certifications can help reinforce better practices (FDA, 2020).

It’s Okay to Use Flavoring—If You’re Honest

The use of synthetic truffle aroma isn’t inherently bad. In fact, it can be a practical, cost-effective way to bring a truffle-like flavor to a wide audience. But the distinction between real truffle and artificial flavor must be made clear. Consumers should know what they’re buying—and paying for.

Transparency fosters consumer confidence, and it respects the culinary heritage of truffles by not cheapening their reputation through deceptive marketing.

Real vs. Faux: How to Tell the Difference

To identify genuine truffle oil, look at the ingredient list:

- Real truffle oil should list actual truffle species (e.g., Tuber melanosporum, Tuber magnatum) and may include visible truffle pieces.

- Synthetic truffle oil often lists “truffle aroma,” “truffle flavoring,” or “ natural flavor”

- Hybrid truffle oils may list a real truffle species and contain visible truffle flakes, but the truffles are sterilized for shelf stability and contribute no real flavor. The actual aroma comes entirely from added “natural flavor”—typically synthetic compounds like 2,4-dithiapentane.

Should You Use Truffle Oil?

That depends on your goal. If you’re aiming to replicate the heady aroma of truffles for a fraction of the cost, synthetic truffle oil offers an accessible option. However, if you seek authenticity and culinary integrity, you might be better off saving up for the real thing or using naturally infused oils made with actual truffles.

Ultimately, truffle oil can be a useful ingredient when used sparingly and with an understanding of its limitations. Knowing what’s in the bottle—and how it got there—helps you make better choices for your palate and your pantry.

However an informed customer should remain aware of the hidden cost of truffle oil.

The Hidden Cost of Faux Truffle:

Culinary and Economic Consequences

Artificial truffle oil might offer a low-cost shortcut to earthy flavor, but its widespread use carries significant downsides—both to our understanding of truffle cuisine and to the livelihoods of truffle producers.

Warped Expectations and Culinary Misinformation

Synthetic truffle oils dominated by a single molecule like 2,4-dithiapentane present a distorted version of what truffles truly are. The result? Diners who’ve never tasted real truffles may develop a misinformed palate, equating the sharp, rubbery sulfur notes of artificial oil with authentic truffle aroma.

This sensory shortcut does more than fool the nose—it limits appreciation for the rich, complex, and subtle aromas of true Tuber species. It can also inhibit culinary creativity, encouraging chefs and home cooks to treat truffle flavor as a one-note novelty rather than a nuanced experience.

Undermining Truffle Growers and Harvesters

Perhaps more concerning is the economic distortion caused by synthetic truffle flavoring. While it creates the illusion of truffle abundance, it offers no benefit to actual truffle farmers, hunters, or ecosystems. These products capitalize on the prestige of truffles while bypassing the people and environments that produce them.

This can depress demand for genuine truffle products, making it harder for small-scale truffle farmers and foragers to compete in a market flooded with artificially flavored substitutes. For those investing years into cultivating Tuber melanosporum or carefully harvesting Tuber magnatum, the challenge isn’t just climate or soil—it’s market confusion.

In short: synthetic truffle oil borrows the allure of real truffles, but contributes nothing back. It erodes the value of authentic products while leaving the truffle community—and the land it depends on—without support.

References

American Chemical Society (2018). Molecule of the Week Archive: 2,4-Dithiapentane, I’m the central figure in the counterfeit truffle-product war. What molecule am I? . Online article.

More InformationCampo, E., Guillén, S., Marco, P., Antolín, A., Sánchez, C., Oria, R. and Blanco, D. (2018). Aroma composition of commercial truffle flavoured oils: does it really smell like truffle?. Acta Hortic. 1194, 1133-1140.

More InformationCullere, L., Ferreira, V., Chevret, B., Venturini, M., Cullere, L., Ferreira, V., Chevret, B., Venturini, M., Sánchez Gimeno, A. & Parmo, D. (2010). Characterisation of aroma active compounds in black truffles (Tuber melanosporum) and summer truffles (Tuber aestivum) by gas chromatography–olfactometry. Food Chemistry. 122. 300-306.

More InformationEpping R, Bliesener L, Weiss T, Koch M (2022). Marker Substances in the Aroma of Truffles. Molecules. 2022 Aug 13;27(16):5169. PMID: 36014409; PMCID: PMC9414745.

More InformationFeng T, Shui M, Song S, Zhuang H, Sun M, Yao L. (2019). Characterization of the Key Aroma Compounds in Three Truffle Varieties from China by Flavoromics Approach. Molecules. 2019 Sep 11;24(18):3305. PMID: 31514370; PMCID: PMC6767217

More InformationMustafa AM, Angeloni S, Nzekoue FK, Abouelenein D, Sagratini G, Caprioli G, Torregiani E. (2020) An Overview on Truffle Aroma and Main Volatile Compounds. Molecules. 2020 Dec 15;25(24):5948. PMID: 33334053; PMCID: PMC7765491.

More InformationNiimi, J., Deveau, A. and Splivallo, R. (2021), Geographical-based variations in white truffle Tuber magnatum aroma is explained by quantitative differences in key volatile compounds. New Phytol, 230: 1623-1638.

More InformationNiimi, J., Deveau, A. and Splivallo, R. (2021). Aroma and bacterial communities dramatically change with storage of fresh white truffle Tuber magnatum. LWT, Volume 51, 2021, 112125, ISSN 0023-6438.

More InformationPatterson, D. (2010, May 16). Hocus-Pocus, and a Beaker of Truffles. The New York Times.

More InformationPiatti, P., Marconi, R., Caprioli, G., Zannotti, M., Giovannetti, R., Sagratini, G. (2024). White Acqualagna truffle (Tuber magnatum Pico): Evaluation of volatile and non-volatile profiles by GC-MS, sensory analyses and elemental composition by ICP-MS. Food Chemistry, Volume 439, 2024, 138089, ISSN 0308-8146.

More InformationSchmidberger, P. & Schieberle, P. (2017). Characterization Of The Key Aroma Compounds in White Alba Truffle (Tuber magnatum pico) and Burgundy Truffle (Tuber uncinatum) By Means Of The Sensomics Approach. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 65.

More InformationSplivallo, R. & Cullere, L. (2016). The Smell of Truffles: From Aroma Biosynthesis to Product Quality.

More InformationSplivallo, R., Ottonello, S., Mello, A., & Karlovsky, P. (2011). Truffle volatiles: From chemical ecology to aroma biosynthesis. New Phytologist, 189(3), 688–699.

More InformationU.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2020). Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Labeling of flavoring agents.

More InformationVita, F., Taiti, C., Pompeiano, A. et al. (2015). Volatile organic compounds in truffle (Tuber magnatum Pico): comparison of samples from different regions of Italy and from different seasons. Sci Rep 5, 12629 (2015).

More InformationWernig, F., Buegger, F., Pritsch, K., Splivallo, R. (2017). Composition and authentication of commercial and home-made white truffle-flavored oils. Food Control. 87.

More InformationContributors

This document was written with the generous contribution of these people. This is a living document and you are invited to leave comments, corrections and contribute further in depth information. Note that the help of Generative AI from ChatGPT was used to assist in drafting, organizing, or summarizing sections of this document.

Ken Fry

Member of the NATGA Research Task Force

Member since September 2019. Member of the Research Task Force. Farming Eagle, Idaho since 1890, Home of Eagle Truffles™️ and Eagle Honey™️

Fabrice Caporal

NATGA Digital Media Task Force lead

Member since 2019, Co-founder of Clos Racines a T. melanosporum orchard in California.